Query: What is the connection between famine (on the one hand) and the current tangle of issues regarding the undersupply or oversupply of lawyers and legal services (on the other)?

Answer: The problem in both instances may be one of distribution.

As to famine…

Thomas Keneally’s new book Three Famines traces the great Irish Potato Famine of the mid-1800’s, the Bengal Famine of 1943, and the Ethiopian famines of the 1970’s and 1980’s.

His conclusion is that overreliance on one source of food leaves a population vulnerable to famine, but it is only when other factors such as inept government or idealogy come into play that the initial trigger balloons into catastrophe.

Hearing Keneally interviewed on NPR’s Marketplace recently reminded me (once again) of the wisdom of so much of Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen’s work. Sen made the case almost 30 years ago that famine is caused not by a lack of food per se but by a lack of distribution of food. Hence his much-repeated declaration that there has never been a famine in a functioning multiparty democracy.

Famine as maldistribution diagnoses the primary cause of the current famine in the Horn of Africa, for example, not as a lack of food worldwide but as food not getting to people who are desperate for it. Which may, according to both Keneally’s and Sen’s insights, have a lot to do with why destabilized and dysfunctional Somalia is at the epicenter of the famine.

Famine as maldistribution also explains why famine in one place doesn’t mean that other places don’t have enough or even too much food. Think, for example, of rising levels of obesity here in the United States.

* * *

As to lawyers and legal services…

What if the undersupply of legal services for poor and moderate income Americans is like famine in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya?

The New York Times recently highlighted a “Justice Gap” – a serious unmet need for lawyers – in the U.S. A 2009 Legal Services Corporation report, for example, concluded that for every qualified low-income person provided legal aid, another person seeking legal assistance is turned away for lack of resources. And that is only those who seek help: The same report estimates that only about one in five low-income person needing legal help receives it.

The report also describes a steep rise in recent years in unrepresented litigants in major personal matters related to housing, family relationships, consumer, and other issues:

“Studies show that the vast majority of people who appear without representation are unable to afford an attorney, and a large percentage of them are low-income people who qualify for legal aid. A growing body of research indicates that outcomes for unrepresented litigants are often less favorable than those for represented litigants.”

Nor is the inability to afford a lawyer confined to the poor. A 1994 ABA study estimated that “most of the legal needs of middle-income households”—a group David Vladeck calls the “unrich”—“go unmet as well.”

BUT…

Over the same period that it has highlighted an undersupply of lawyers and/or legal services, the New York Times has also run articles about the oversupply of lawyers, especially lawyers at large corporate firms. These firms have a surfeit of lawyers, just like Americans have a surfeit of food.

Maybe, just maybe, as with food famines, there is a distribution problem here.

If so…

– Do unauthorized practice of law regulations that allow lawyers alone to provide legal services have the same effect as restricting a vulnerable population to one food source?

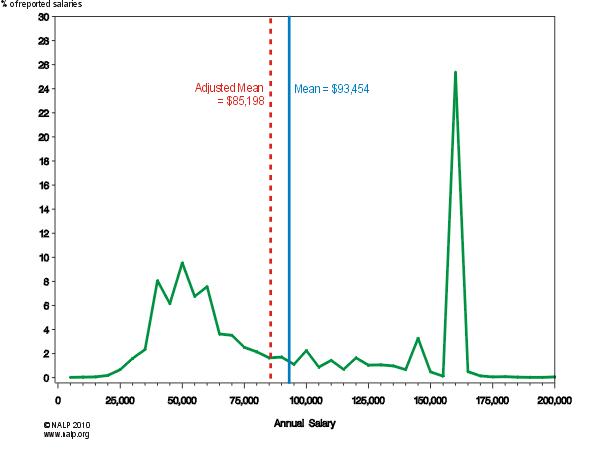

– Could both the oversupply and the undersupply of lawyers be related to the bimodal starting salary distribution of lawyers (see below) that has emerged over the past 20 years? (Over the past generation, the proportion of lawyers who represent institutions

– Could this salary distribution be related to increasing levels of inequality in the U.S. overall since the late 1970’s? (Wealthier Americans can pay top dollar to protect their interests, while the poor and “unrich” have seen their real incomes shrink.)

– Do rising tuition costs and law schools as “cash cows” for universities contribute to the “law famine” by saddling new lawyers with debt that mandates right-hand peak salaries—even for young lawyers who might otherwise be drawn to left-hand peak practices?

Oh, what a tangled web…