Have you ever wondered about the women who ran the households of the Founding Fathers while they Declared Independence, fought the Revolutionary War, drafted and ratified the Constitution, and then governed the fledgling United States?

We know quite a bit about Abigail Adams, in large part because of the vibrant letters she and husband John wrote each other—letters that include Abigail’s famous admonition to “…remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.” (John responded, “As to

But Abigail Adams is the exception. More often, modern efforts to construct narratives about these women founder because of the lack of contemporary evidence.

Martha Washington destroyed the letters she and George wrote to each other. James and Dolley Madison wrote few letters because they spent little time apart. One summary of biographical information about Alexander Hamilton’s wife admits, “[m]ost of the information on Elizabeth Hamilton must be gleaned from biographies written about her husband.”

Similarly, little beyond the essential facts is known of Martha Jefferson. Sally Hemings, a slave owned by Thomas Jefferson who is now generally acknowledged to have borne 6 children by him in the years after Martha’s death, has garnered more attention, and fictionalized accounts have sought to pierce the dual curtains of race and gender.

The late sociologist Elise Boulding referred to the silence of the historical record about women as the “underside” of history. Boulding contended that women have always been equal actors on the stage of history but that the record of our parts routinely evaporated when the script was eventually written down. We are left with a partial story, a play with half of the lines missing.

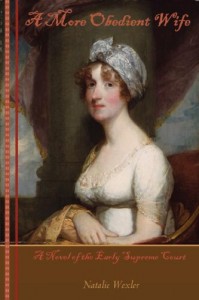

A More Obedient Wife by Natalie Wexler is a wonderful endeavor to fill in a few of these lines.

After clerking for Justice Byron White (full disclosure: she passed off the baton of “female clerk in the chambers” to me in mid-1985), Wexler worked at the Supreme Court Historical Society on a Documentary History of the early Supreme Court. While there, she came across letters written by Justices James Wilson and James Iredell of the first Supreme Court and by their wives, Hannah Iredell and Hannah Wilson.

James Wilson of Pennsylvania, in addition to being one of the first Justices, signed the Declaration of Independence, was an active participant at the Constitutional Convention, and gave a speech in the ratification process that is widely regarded as being at least as influential at the time as The Federalist Papers.

James Iredell of North Carolina, though not a participant in the essential events of the Founding, was an early Patriot who strongly supported the Constitution and served on the Supreme Court even before North Carolina’s ratification became effective (it did so only with the adoption of the Bill of Rights). On the Court, his solo dissent in Chisholm v. Georgia formed the basis for the Eleventh Amendment.

Wexler became interested in writing biographies of Hannah Wilson and Hannah Iredell, but she realized that it wasn’t possible: “There simply isn’t enough information to work from; women’s lives weren’t considered important enough to document in detail.” Instead, she wrote a novel that weaves together excerpts from actual letters and fictionalized accounts based on historical research. The result is a vivid and grounded picture of the early Supreme Court and its social context.

Yellow fever in bustling Philadelphia; land speculation of the “frontier” on a scale that makes Wall Street today look timid; slavery in everyday life; debtor’s prisons; frequent pregnancies and fatal childhood diseases; early travelling requirements and conditions for the judicial circuits; current afflictions such as alcoholism and agoraphobia as seen through 18th-century eyes; the arranged marriage of the Iredells and the infatuation of the Wilsons—all of these bring to life the Supreme Court (and the United States) in its infancy.

When I suggested to my book group here in Omaha that we read A More Obedient Wife, I could tell that they were humoring me in selecting it: How interesting could a book about the early Supreme Court be!?

When we met last week, however, the verdict of this group of mostly non-lawyers was that Wexler’s book was a great read as well as a window into an unfamiliar part of history!

More than that, it provides a perspective on important historical events that too often goes missing—the perspective of and from the underside.